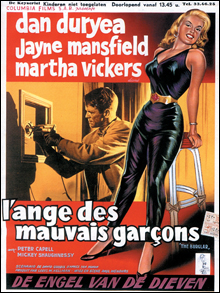

THE BURGLAR: Jayne Mansfield pops out from the Belgian poster. |

The Brattle’s “Rare Film Noir” festival spotlights what makes the experience of going to movie revivals irreplaceable. The sparkling new 35mm prints underscore the dazzling, sometimes shocking, contrast of black and white, light and shadow, that is the visual trademark of noirs. Enterprising B-list directors of the ’40s and ’50s who were lucky enough to get assigned these seedy urban thrillers used them not just as a training ground but as a way of showing off their technique and imagination, in the hope of elevating their status at their home studio. The same was true of cinematographers, and these nine showcased pictures pay tribute to some of the best: Lee Garmes (The Captive City, July 25), Burnett Guffey (Nightfall, July 18), Hal Mohr (The Big Night, August 8), John Alton (Witness to Murder, July 25). Even less-heralded DPs manage to turn their trim budgets into filmic virtues. Look at the velvety quality of the night-time streets punctured by halo’d auto lights in the tense police procedural Between Midnight and Dawn (August 15), which was shot by George E. Diskant, or the way William Steiner focuses on the textures and proportions of an abandoned apartment building’s interior, where schoolboys hang out in the opening scene of The Window (August 22), to emphasize its dangers.A particularly striking example of what a theatrical photographer like Alton — here working with the game director Roy Rowland — can accomplish is the expressionistic sequence in 1954’s Witness to Murder where Barbara Stanwyck is confined to a psychiatric ward for observation. In the early hours of a windy, storm-threatened LA night, Stanwyck wakes up to see her neighbor (George Sanders) strangle a call girl in the building across the street. He’s smart enough to remove the body and doctor the evidence, and when she persists in trumpeting her story, he goes on the attack and succeeds in making her look like a delusional hysteric. She wakes up in a room framed by darkness, where the sweep of light is so intense, it silhouettes her three loony roommates and the unsmiling nurse with a syringe at the ready the moment Stanwyck protests.

The casting of the forthright, earthbound Stanwyck is part of what makes Witness to Murder so effective: when she begins to question her own sanity, you really feel none of us is safe. In The Window, from 1949, a boy (Bobby Driscoll) with a penchant for telling melodramatic whoppers sleeps out on the fire escape on a sultry night and sees the couple upstairs (Paul Stewart and Paul Roman) rob and kill an itinerant — and of course no one believes him, neither his beleaguered parents (Arthur Kennedy and Perry Mason’s Barbara Hale) nor the local cops. Driscoll’s increasingly imperiled situation, like Stanwyck’s, suggests how quickly, in movies like these, a seemingly benign world can turn predatory and violent. (In the unnerving climax, the movie returns to that abandoned building that has been merely a playhouse for Driscoll and his friends.)

PUSHOVER: Kim Novak dominates Fred MacMurray in this Finnish poster. |

The Brattle has always extended the definition of film noir to enable broader programming; The Burglar (August 8), for instance, is really an arty heist picture, though it does feature noir mainstay Dan Duryea in the lead. The most traditional noir among these nine is Pushover (1954; July 18), where Fred MacMurray plays a cop who woos a bank robber’s mistress (Kim Novak) in order to trap her boyfriend — and then falls for her so hard that he agrees to kill the mug so he and the girl can live together on the purloined cash. It sounds like a retread of MacMurray’s most famous movie, Double Indemnity, and in many ways it is, but the presence of Novak (in her first major role), with her air of melancholy and wrecked innocence, gives it a distinctive feel. MacMurray was perfect for this kind of hard-boiled material: he had such a regular-guy affability that he could take his characters into fairly murky territory without losing your affection. (Among contemporary actors, Bill Paxton comes closest to effecting that sort of identification from audiences, in noirs like One False Move and A Simple Plan.)One of the pleasures of becoming acquainted with movies like these that, unlike Double Indemnity, have slipped off the radar is that you never know who’s going to show up in them. Nobody Lives Forever (August 1) stars John Garfield as a confidence man who courts wealthy widow Geraldine Fitzgerald for her loot and then falls in love with her. The stars aren’t a match, though both are highly watchable for their individual talents, and Fitzgerald is especially poignant in the scene where she learns that the man she has grown to adore has been setting her up. The real ace in the cast, though, is Walter Brennan as Garfield’s loyal pal, a one-time con artist reduced to picking drunks’ pockets. A young Anne Bancroft — already effortlessly elegant and buzzing with that electric current that ran through her great performances in the ’60s — is the Hollywood model who touches hero Aldo Ray for the price of a drink in Nightfall (1956) and thus is targeted by the same murderous duo Ray barely escaped from out in Wyoming. Brian Keith, that peerlessly economical character actor, plays one of the pair of villains. (The skillful director is Jacques Tourneur.) Edmond O’Brien is the leading cop in Between Midnight and Dawn, which features the now-forgotten ’50s TV icon Gale Storm, at the outset of her career (the movie came out in 1950), as the daughter of a policeman killed in action who, against her better judgment, finds herself in love with O’Brien’s partner (Mark Stevens). One of the incidental pleasures of Pushover is the appearance of the vivid Dorothy Malone as Novak’s next-door neighbor, who attracts the notice of MacMurray’s partner (Phil Carey); their romance is, in noir terms, the decent love story the movie juxtaposes with the illicit, doomed one at the center of the film.