A worthy life of Kingsley Amis

By JAMES PARKER | June 12, 2007

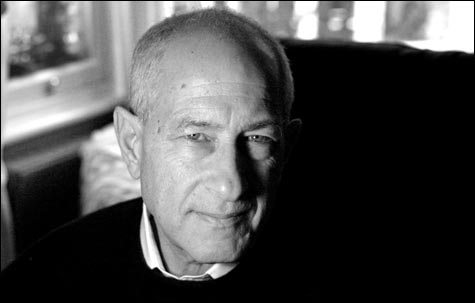

SMACKDOWN: Leader gives Martin’s dad the full treatment, in all his fêted — and fetid — glory. |

Eight hundred pages long, with another 200 pages of notes, The Life of Kingsley Amis is stunningly comprehensive. That it is also very readable owes as much to Zachary Leader’s easy, candid, percipient style (like a marathon runner, he covers the distance at an even jog) as to the never-less-than-interesting exploits of his subject. Kingsley Amis was the most fêted and notorious of post-war British novelists: his prose, with all its willed inelegance and anti-lyrical lumpiness, gave his literary generation the same shock of delight that his son Martin’s would to the generation that followed. The savage modern laughter of 1954’s Lucky Jim, a campus novel that seemed to burn down the campus, was a sound not previously heard. Was Kingsley a nice man? Not particularly. As presented by Leader, he was a neurotic trapped in the (steadily thickening) body of a bon vivant. Half of his life was a porky picaresque — shags in the greenhouse, pranks in the letters pages, drunken scrapes and flare-ups. The other half was a cloud of existential dread. Anxiety was constant: he was afraid of the dark, of madness, of air travel, of being alone. Asked by the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko whether he was an atheist, Amis is said to have replied, “Well, yes, but it’s more that I hate Him.”

And then there was what we might call the third half: his life as a writer. Amis was a steady worker with a radical mistrust of romanticism. Any sort of exhibition or hint of transcendence went down badly with him: he objected to the “high idiosyncratic noise level” in Nabokov’s Lolita, and he ascribed the “unidiomatic” specialness of Saul Bellow to the author’s ethnicity (“Bellow is a Ukrainian-Canadian, I believe”). We see the strength of Leader’s method when he traces these anti-predilections — useful at first, a pain by the end — back to the counsels of the Reverend C.J. Ellingham, one of the teenage Amis’s Classics dons at the City of London School. More than three pages are given to Ellingham’s 1935 manifesto Essay Writing: Bad and Good, but they turn out to be three pages very well spent. “Do not try to bluff the reader,” preached the Reverend Ellingham. And again, in a chapter called “The Critical Essay”: “Be scrupulously honest. A good book for you is the book which you enjoy, not the book which you imagine the reader will expect you to enjoy.” Amis, in later life a loud and highbrow-baiting enthusiast of James Bond, The Terminator, and the novels of Dick Francis, learned these lessons almost too well.

Topics

Topics:

Books

, Media, Books, James Bond, More  , Media, Books, James Bond, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Dick Francis, Saul Bellow, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Less

, Media, Books, James Bond, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Dick Francis, Saul Bellow, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Less